Could timber skyscrapers rise across Asia Pacific?

More countries across the region, including Japan, Australia and New Zealand, are taking an interest in building ever high timber structures.

Japan is no stranger to wooden buildings; it’s home to Horyuji, a pagoda noted for being the oldest wooden structure in the world

In the coming years, the country could boost its wooden architecture credentials further amid plans for the world’s tallest wooden skyscraper, rising 70 storeys and 350 metres above Tokyo – a height that would also take the title of Japan’s tallest building. The only catch is that the architects have an end date of 2041 in mind – giving plenty of time for other cities to plan for their own wooden skyscrapers.

Indeed, timber is becoming an increasingly popular building material in cities across Europe and North America.But the ambitious scale of Tokyo’s W350 project makes it almost four times higher than the current tallest wooden structure, the 18-storey Brock Commons Student Residence in Vancouver, Canada.

“In line with the ideals of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investing through the development of sustainable cities and communities, I believe these structures will spark the interest of cities and developers to create more wooden skyscrapers in Tokyo and in other Japanese cities,” says Naoko Iwanaga, Research Manager at JLL Japan.

“Wood has always been a sophisticated material in traditional Japanese architecture and we now possess the technology for strong, fire-resistant wood to be used in taller buildings.”

Japanese construction firm Shelter has manufactured a wooden pillar able to withstand fire for three hours. And it’s recently been approved by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism for use in buildings with 15 or more storeys.

The Japanese government is backing wooden construction materials. In 2010, the Promotion of Use of Wood in Public Buildings Act, came into force and required all government buildings up to three storeys high to be constructed with wood. Last November, the government announced plans for a new tax that would boost the conservation and management of forest as well as set up a forest bank to rehabilitate and redevelop abandoned forest.

“The government aims to contribute to the development of a low-carbon society in part through dissemination and awareness raising of cutting edge technologies relating to wooden architecture. The use of wood is promoted not only as a sustainable material, but one maintaining the forestry-cycle-system and representing harmony with nature,” observes Iwanaga.

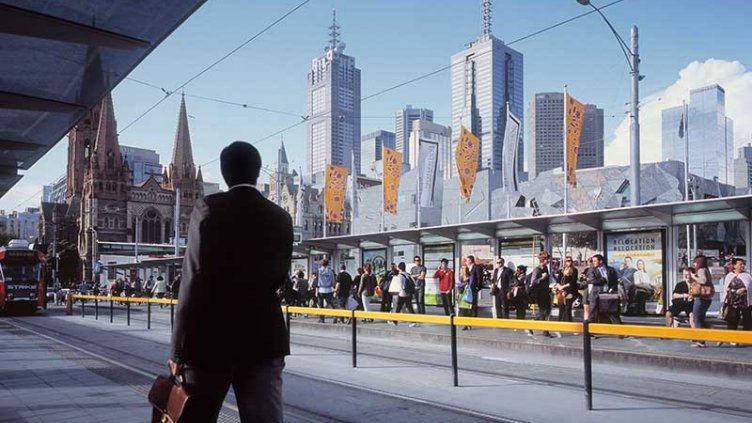

Timber time for Australia

Other countries in Asia Pacific are also taking a keen interest in timber. In Australia, several cities are in a race to construct wooden buildings that will take their place in the history books. Sydney’s International House is the country’s first engineered timber office building and a sister building is being built in the city as well while Brisbane will boast the world’s tallest wooden office tower when 5 King Street is finished this year. Melbourne already has Forte and The Dock, an apartment tower and library respectively made of cross laminated timber and recycled hardwood.

Simone Concha, Sustainability Director, JLL Australia explains that the drive towards timber in Australia is partly due to the fact that wooden buildings are quicker to build and lighter to construct, which equates to reduced overheads, and lower material cost for foundations and footings. They also have a smaller carbon footprint and reduced waste compared to using steel or concrete.

“Moreover, the timber used is sustainable-source certified and it is a renewable product, unlike concrete and steel, which are manufactured using finite resources,” she says. However it’s still a while away before timber becomes the default material of choice, she adds “Concrete and glass will continue to play a big part in construction. It takes time to change construction ‘norms’.”

Changes are happening in Australia though. Legislation was amended in May 2016 to allow timber structures up to 25 meters – or eight storeys tall – within the National Construction Code. Meanwhile, construction techniques and materials that reduce carbon emissions will become more valuable as part of Australia’s commitment to the Paris Agreement. Melbourne’s new Climate Change Act 2017, for example, aims to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. And the 2017 launch of Australia Research Council’s Future Timber Hub will further help accelerate the uptake of timber by promoting research into timber construction and developing timber products to suit the Australian construction industry.

Building a following across Asia

But aside from developments in Australia, Japan and New Zealand, the rest of region is yet to embrace timber buildings.

“It takes time to build up critical mass in terms of experience, willingness to pursue this style of design,” observes Matthew Clifford, Head of Energy and Sustainability Services, JLL Asia Pacific. “There are still relatively few experienced designers, engineers and architects specialized in building wooden skyscrapers. This means this is less likely to be suggested as a construction option, and may take a particularly committed client to push for timber.

“Equally, if clients are less open to trying new things, this may just not catch on, meaning we get a few one-off interesting buildings, but the bulk of the industry follows traditional building practices.”

The use of wood has also been dogged by some controversy. Tokyo’s Olympic Stadium has been accused of using wood linked to deforestation. “It is very important that timber is sourced from certified plantation forests using systems such as Forest Stewardship Council certification,” says Concha. “For wood to take off, it’s key to ensure there are alternatives, such as bamboo (a fast growing grass, not a timber) as sources as well.”

For now, while wooden buildings may become a feature of some city skylines in Asia Pacific, they’re far from being a common sight.